HENDRIKUS (Henny) Nieuwendyk is a Dutch migrant who, like many, chose to find a new life in Australia.

He is well known to many in Mount Gambier because of his numerous achievements.

After a medical diagnosis found he had an enlarged heart he turned his thoughts to living in a warmer climate, leaving his home in Holland in 1958 to travel to Sydney before settling in Mount Gambier.

He had a long business career at Youngs The Man’s Shop, but also achieved great success on the sporting field as a champion soccer player who played at elite level in Holland, Adelaide and then became a hall of fame member as a player, coach and life member at International Soccer Club.

Then in the early 1960s he decided to play Aussie Rules and in 1963 made his debut in the East Gambier A Grade team.

He also played a significant role in basketball, winning three successive premierships with Trotters in A Grade from 1966 to 1968 and has been a playing member of the Mount Gambier Golf Club for more than 45 years where he won the seniors championship on two occasions.

In the 1970s, Henny put the club on the national map and the front page of numerous newspapers in a publicity stunt, when he played the entire 18 holes using only four clubs and ran from shot to shot.

He played the entire 18 holes in 54 minutes (usually it takes four hours) and had 84 off the stick.

He helped raise $41,000 for multiple sclerosis by riding 700km in 10 days in Vietnam in 2010 and was nominated to carry the Olympic torch around the Blue Lake during the lead-up to the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

He has also been a hard-working member of the Gambier City Lions Club for almost 35 years.

His achievements led him to being named 2015 Mount Gambier City Council Australia Day citizen of the year but what many may not realise is that Henny created fame in another sport, for which today, he is still revered and remembered.

It occurred back in his home country of Holland in February 1956 – he was about to race in Holland’s greatest outdoor ice skating race.

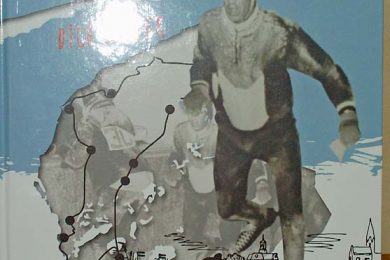

It is called the “Elfstedentocht” or “11 Cities Tour” (Marathon) and travels through 11 cities of Friesland in Holland.

The race involves skating through 200km of Friesian landscape on streams, canals and small rivers which had frozen over during the European winter.

The race is held only when the “Icemaster” – the person who tests the depth of the ice – determines it is safe for the 300 participants, their crew, officials, scooters and motor bikes which follow behind, to take part in the race.

It is the dream of many Dutch ice skaters to take part in this once-in-a-lifetime experience of being able to participate in the race and be awarded the Participant’s Cross.

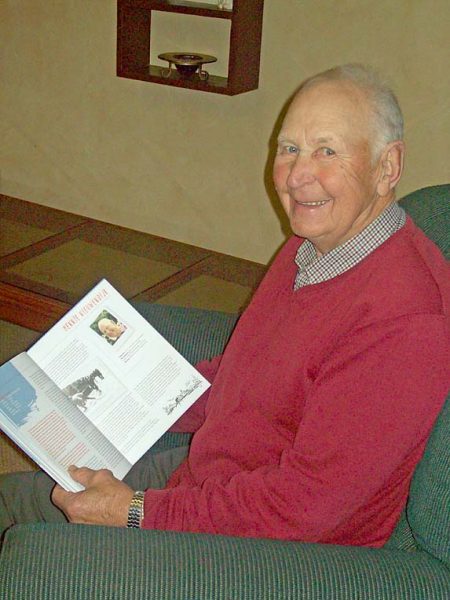

Last year an A4 sized hard-back glossy-paged book on the history of the famous race was published and Henny’s exploits in what he achieved in that race are highlighted in great detail.

This is his story.

Henny and his brother had completed a 90km ice skating race near their home town on Sunday, February 12, 1956 and the following day at work he heard a radio announcement the 11 Cities Tour would be held the following day, Tuesday.

He immediately requested and was granted the day off work and then rode his bicycle 20km to his home at Nes aan de Amstel to seek permission to join the race.

At first his parents tried to change his mind but eventually his father gave him money for bus fares and train tickets while his mother made alterations to his skating trousers by stitching a leather patch in his leggings to help ward off the expected minus 15 degree temperatures.

He travelled by bus from his home to Amsterdam Central Station and boarded a train which was packed with other skaters from all parts of the country as they headed for Leeuwarden.

After arriving at 7.30pm he went to the registration bureau and after convincing officials he was 19 years of age (the minimum racing age was 18 and he looked young for his age) he was accepted as a starter for the next day’s race.

Luckily he was taken in by an accommodating family when they heard he had nowhere to sleep and was racing the next day.

The race started at 5.30am with 300 participants, but most skaters had back-up crews or teams, plus had food supplies and reserve equipment – Henny was on his own.

After a 100-metre walk to the canal, skaters put on their skates and the racers took off into the dark, as dawn was still several hours away.

Snow then started to fall in the minus 15 degree temperature.

There were several check points where skaters received a “stamp” and the first of these was at the 22km mark.

“At that point I was simply following other skaters and had no idea what position I held in the field,” Henny says in the book.

What he did know was that he was among a bunch of very fast skaters – among the best he had seen.

Soon it was on to Slaten, then Stavoren and by then the pack had dropped back to about eight or nine and Henny was still holding his own, but unsure where he was in the overall field.

As he neared one point, he was in a group of about nine or 10 skaters, when they suddenly heard spectators yelling “sand, sand, sand”.

The group of skaters was travelling at top speed and so hit the sand with disastrous results.

They all fell over and over again, wasting valuable time which later would prove crucial.

(Later officials claim this part of the race gave the leaders a 30 minute advantage as there was no sand on the ice as they went through. There was some discussion whether the sand had been deliberately thrown on the ice to help the leading racers).

“It was a competitive race and there were suggestions it had been deliberate and placed on the ice after the leading pack passed through,” Henny said.

They passed Hindeloopen, Workum, Bolsward on their way to Harlingen.

At about that time Henny had cleared out from the others and was skating alone.

In the meantime, other skaters had support crews and were handed drinks and food by staff riding on scooters or standing by the side of the canal.

By this time Henny’s body was craving drink and food and had to rely on some food rations he took with him from breakfast at his hosts’ home, but they were soon gone.

His body was telling him it could not go on but somehow his determination drove him onward.

With his muscles throughout his body aching from the pressure of non-stop, skating over such a distance he put this to the back of his mind and powered on with his head and shoulders bowed forward, hands clasped behind his back, working his legs in perfect motion as his skates sliced through the ice.

“While I was skating in the middle of the vast “Friesian polder” I found myself alone and began to doubt if I was on the right course because I had not seen any skaters behind or in front of me at that time,” he says in the book.

Spectators came to the rescue when they shouted encouraging chants which inspired him and they told him he was only 25 minutes from the next check point at Bartlehiem.

However, serious doubts and confusion set in when 20 minutes later another spectator gave him the same information.

Then it was on to Dokkum, where skaters made the turn and raced back to Bartlehiem – it was then, for the first time, he realised his position in the overall field.

As he skated to Dokkum, coming back on the return journey he saw a pack of fast skaters, which were the leading group.

Sensing he was the underdog, spectators were cheering from the sidelines and this encouraged Henny to increase his speed in an effort to close the gap and by the time he reached Dokkum to make the turn there were thousands of spectators on the canal banks cheering him on as he skated alone as he had done for most of the race.

“I felt really good at this point and now I was back on the straight, heading towards Bartlehiem – I felt like I was flying,” Henny says in the book.

As Henny drove his legs through the pain barrier he passed through Bartlehiem towards Leeuwarden and still on his own, he started to feel lonely, when some spectator skaters joined alongside, encouraging him as he raced to the finish line.

On the approach to Leeuwarden the number of spectators on the canal banks grew and by the time he neared the city and the finish line there were more than 50,000 people standing and cheering on the skaters.

In what will go down in history as one of the greatest races of all time in the history of the 11 Cities Tour, the leading group of five skaters decided to cross the line together, each holding the other’s hand, thereby forcing a five-way dead-heat.

Henny crossed the line, as he had done for most of the race – on his own – and was credited with an official 12th placing, about 30 minutes behind the winners which was the time he lost when he fell.

He finished 12th out of a field of 300 and received the Participant’s Cross which he still wears around his neck today.

Following the race he made the long trek back to his home arriving about 10.30 that night and then rode his bicycle 20km to work the following day – it was all in a day’s work.

Henny’s incredible performance did not go unnoticed and was invited to race in other major ice skating events in the coming months.

They included the 100km Amsterdam City Canal Race and the Amsterdam Bos Race, where he finished fourth.

He was later invited to train with the Dutch national ice skating team and after training for six months a medical diagnosis revealed his enlarged heart and low heart beat and was told to cease training for two years.

That was the catalyst which led Henny to migrate to Australia seeking a warmer climate and lifestyle change and it was where he later met his wife Pat (nee Madden).

They have three children, Kristyn, Mary-Ann and Monique.

The book, which has been distributed widely in Holland and Europe, contains hundreds of photographs and stories on many of the champion skaters who have become Dutch icons after competing in the great race over the past 50 years.

The author Dick Backer tracked down Henny from Holland to complete the chapter on a young 19-year-old who nearly won the race without any support team or team members.

In Holland and parts of Europe Henny Nieuwendyk remains a legend and his solo performance is still rated highly in Holland and this is evidenced by his inclusion among the “greats” of the 11 Cities Tour.